How can you know what’s morally right and what’s morally wrong? I think the answer is simple: you can use your conscience, i.e. your intuition. We all have an innate understanding that some actions are right and some are wrong, and we can clarify this understanding with the use of reason.

Recently I’ve had a back and forth with two philosophy enthusiasts,

and . The disagreement revolves around the role of moral intuition in moral philosophy.Clarifications

First, a few clarifications in response to some claims that Shtein made in his recent post.

I don’t consider myself a “virtue ethicist”.

I don’t hate fat people, but I do want them to stop being fat.

I am not totally opposed to homosexuality and I think it is sometimes acceptable for homosexuals to have sexual relationships with each other. I do find homosexual acts disgusting and, more importantly, there is something uncanny and morally alarming about some of the personality characteristics of many gay men. Clearly, the avoidance of disease was one reason why we evolved a disgust reaction towards homosexuality, but I suspect it was not the only reason. Periods of homosexual acceptance seem to go hand in hand with decadence. It seems to have played a role in the decline of Greece and Rome. Perhaps ancient tribes which tolerated homosexuality among their members were less cohesive and were beaten by tribes that were “homophobic.” But there have been homosexuals among the great and good as well, such as Ryan Faulk, Leonardo Da Vinci and Pim Fortuyn. My position on homosexuality is the same as Richard Nixon’s. I think some people are born that way and they should be free to do what they want in private; it just shouldn’t be publicly normalized or presented as an equally good alternative to heterosexuality.

While I don’t think that homosexuality should be in the public square, I also don’t think it’s anywhere close to the most important socio-political issue at this time, so after this post I don’t intend to write anything more on the subject.

I love cheesecake.

Using Moral Intuition in Moral Philosophy

In a recent post, Shtein argued that his view (Utilitarianism) uses intuition correctly because it appeals to the meta-ethical intuition that pain is bad while my view uses intuition incorrectly because it appeals to object-level intuitions that certain specific things/actions are good or bad.

But this totally misunderstands how moral intuition ought to be used1!

Like Michael Huemer, I believe that the right way to do moral reasoning is to start from clear cases and then evaluate similar cases based on whether or not there are any morally relevant differences between them and the clear cases.

I’m not saying that we should consult our object-level intuitions on each case in isolation. I agree with Shtein that that would be “just a bunch of random crap.”

Instead we should take a very clear moral case about which the moral intuition is very strong and universally agreed upon. Then we should judge similar cases by comparing them to the clear case and thinking about whether or not the differences between the two cases are morally significant.

For example, suppose Smith throws Jones off a building. That seems clearly wrong. Now let’s change the situation slightly. Suppose Smith throws Jones off a building because Jones is gay. Still seems clearly wrong. Intuitively, a person’s sexual preference is not a legitimate reason to throw them off a building. Now suppose you learn that Jones is a convicted murderer, or that Jones is not a murderer but there is a giant trampoline. Those differences do seem morally relevant.

Peter Singer uses the same kind of reasoning in his famous “drowning child” essay2. He starts with a clear case: the case where you pass a child drowning in a small pond. He then compares other cases, i.e. donating money to famine relief, and concludes that the differences between these cases and the clear case are not morally relevant. Singer writes:

It makes no moral difference whether the person I can help is a neighbor's child ten yards from me or a Bengali whose name I shall never know, ten thousand miles away3.

Now let’s take another case. Suppose that Arnold likes to eat his own poop in public places such as malls and restaurants. Most people will agree that it is not good to do this in public. It is rude at the very least. And it may be so bad that it should be prohibited by law on public decency grounds. Now we’ll take a related case. Suppose that Bert is gay and he likes to kiss and touch his many boyfriends in public places such as malls and restaurants. Both Arnold and Bert are doing something that will cause most members of the public to experience a disgust reaction. Are there any morally relevant differences between the two cases? Well for one thing, Bert may have been born with a genetic predisposition to be homosexual, but we can stipulate that Arnold was also born with a genetic predisposition to enjoy poop-eating and it still seems that Arnold ought to keep his poop-eating activities in private.

It seems that the real reason for the difference in our initial reactions to the Arnold and Bert cases is that over the past few decades there has been a highly influential homosexual activist campaign. When our grandparents were born most people would have thought that both Arnold and Bert’s activities should not be allowed in public. There would be no philosophical puzzle for those old-times folks because their intuitions about the two cases would be consistent; they thought both should not be allowed in public. If the reason why we feel differently about Arnold and Bert is merely because of the contingent fact that our culture happened to have a homosexual rights movement rather than a coprophagia rights movement, then our differing intuitions between the two cases are hard to defend.

For a person who grew up in a modern Western culture, it may be unintuitive at the object-level that public displays of homosexuality would be wrong. But when you consider analogous cases like public poop-eating, the object-level intuition that gay PDA should be allowed (an intuition I initially shared) should be discarded in favor of the clear-cases intuition that public poop eating is bad and the intuition that it’s not morally relevant that we happened to have a gay-pride movement rather than a coprophagia-pride movement.

Rebutting an Objection

Q: Should it be illegal for people with deformities to leave their homes?

A: It’s not unheard of for people with deformities to become shut-ins because they are ashamed to be seen in public. That is an example of the sentiment that public decency ought to be upheld, but it’s too extreme in this case. Requiring someone to never leave their home is a huge imposition, but requiring someone to keep displays of affection in private is not a huge imposition, so people with deformities can leave their homes, but homosexuals should refrain from displays of intimacy in public. They can keep it in private.

Moral Disagreement is Mostly a Myth

My intuition-based view could potentially run into a big problem: What if people disagree about the right thing to do in a case that I considered a clear case?

One might think that gay men don’t share the intuition that homosexuality is disgusting, but one would be wrong! It’s a very common experience for gay men to initially feel disgust and shame at their attractions, but then gradually reduce those feelings of disgust and shame as they expose themselves more and more to homosexual acts and homosexual culture. Homosexual youtuber and political commentator Brad Polumbo has said that he and most other gay men he knows spent much of their youth trying to figure out ways to not be gay.

The extreme acts of the homosexual bathhouses of San Francisco in the 1980s would disgust nearly all straights, and they also disgusted earnest young gay men who came from Middle America and saw the bathhouses for the first time.

Here’s an account (derived from firsthand interviews) from And the Band Played On, Randy Shilts’ book on the AIDS crisis:

“It looks like that guy has his arm up the other guy’s ass.”… Kico was sickened. He had heard a lot about the bathhouses since moving to San Francisco five weeks before. The local gay papers were filled with ads and catchy slogans for the businesses… Kico had moved from Wisconsin to San Francisco with a clear sense of what being gay meant. He figured gay people dated and courted; you certainly never went to bed with someone you just met… the young man had led a relatively sheltered life. Suddenly, he was very confused… The Cellblock Party, just a few blocks from a rally where speakers were so loftily discussing the finer points of gay love, was like some scene from a Fellini film, intriguing and inviting to the eye, but altogether repulsive to Kico. The scene was even more alienating because these guys were so attractive…

Kico’s first impression of the San Francisco bathhouses was moral disgust. I believe that is everyone’s first impression. But if you choose to press onward in spite of disgust, you will gradually lessen that disgust reaction, and maybe eliminate it altogether. Once you have modified your reactions in this way, it is sometimes hard to even remember that you used to have different reactions.

I believe that nearly everyone has an inborn moral disgust reaction to homosexuality. In my initial article that Shtein responded to, I cited a study which found that men’s disgust reaction to images of two men kissing didn’t depend on their stated pro-gay or anti-gay beliefs. I.e. even leftie men who express pro-gay sentiments find homosexuality disgusting. Young men who were born with homosexual attraction are in the unenviable position of having sexual desires that collide with their natural feelings of disgust. I have a lot of sympathy for people in that situation. The best approach is probably to encourage “bisexual” people to choose a heterosexual lifestyle and accept some people as unchangeable homosexuals while acknowledging that homosexuality is less than ideal - it’s not as good as heterosexuality.

Here’s another example of a time when alleged moral disagreement turned out not to be real: During the BLM riots of 2020 some said that rioting is understandable as the “voice of the unherd” while others said that rioting is never justified and rioters should be shot on sight. But in November of 2023 there was a riot in Dublin after a Middle Eastern foreigner stabbed three young Irish girls. The rioters assaulted police, smashed storefronts and burned buses. But the riot had one very unusual feature: the rioters were white and were motivated by a right-wing cause célèbre, not a left-wing one. Suddenly many people had an astonishing change of opinion on the moral question of justified riot. White nationalists started talking about how riots are the voice of the unheard and left-wing Irish politicians who had praised the BLM rioters called for the Dublin rioters to be crushed with overwhelming violence. Obviously, in 2020 when the the White nationalists disagreed with the left-wing politicians about the BLM riots, they didn’t actually have different moral intuitions about the morality of rioting, they just had different tribal loyalties4.

I think that moral intuitions in clear cases are pretty much universal. Nobody genuinely lacks the intuition that it’s wrong for Smith to throw Jones off a building. Everyone starts out with an intuition that homosexuality is not as good as heterosexuality - but that intuition can be weakened or beaten out of them if they live in a society where they are sternly morally scolded for having that intuition, and told to repress it.

Abrahamsen on Poop Eating

Silas Abrahamsen says

…eating humans is not intrinsically wrong. That isn’t to say that I don’t find the thought of eating human flesh incredibly repulsive—I definitely do. But I also find the thought of eating a big, fat, steaming turd or the thought of my grandparents having sex incredibly repulsive, but those certainly aren’t wrong!

Personally, I think there might be something wrong with eating poop. I said so on Substack and Abrahamsen replied asking if it was because eating poop might spread disease or something. But Abrahamsen is still missing the point. It’s not just about disease.

If you’ve gotten this far in the article you’re probably interested in moral philosophy and you probably have a preferred moral theory. But take just a few minutes to set aside your moral theory and take a step back and ask yourself what you really feel about this. Consider a person sitting down at their kitchen table and eating human poop. Do you really intuit that that’s totally morally unproblematic? No more morally questionable than eating a plate of carrots?

Natural Law theory posits that things have “proper functions” and that when you use something (especially part of your own body) in a way that goes against its proper function, that is morally wrong because it is “disordered.” At first glance, this sounds very silly. It is easy to reject Natural Law - until you encounter someone doing something seriously disordered.

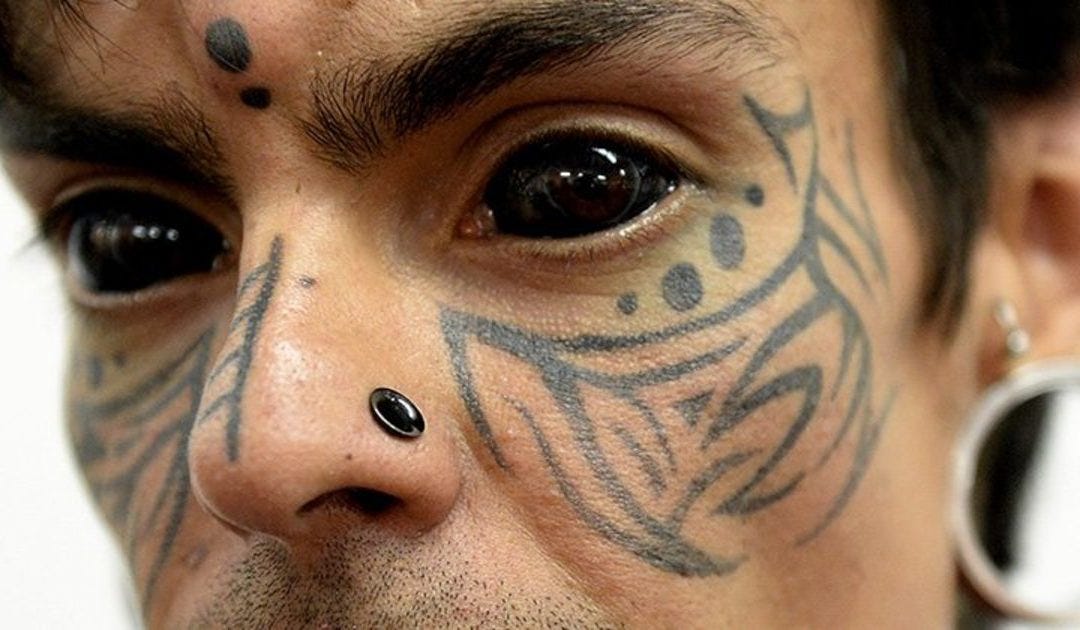

One thing that changed my mind and made me more sympathetic to some Natural Law concerns was the phenomenon of eyeball tattooing. This is a personal choice that affects only yourself, but it really seems like a wrong thing to do.

There is a fellow named Satan Prado who has had horn implants in his head as well as eyeball tattoos, face tattoos, metal teeth and tusks, and nose removal so that he can look like Satan. I think that’s morally problematic. The term “disordered” seems applicable.

And I also have an intuition that there’s something morally not quite right about eating poop. Sure, it’s not wrong in the way that murder or theft are wrong, but there still seems to be something wrong with it. If there were a person who habitually ate poop, I would think there was something morally suspicious about that person’s lifestyle - even if they sterilized the poop with radiation to avoid spreading disease.

And this brings me back to the original (and far more important) subject on which Abrahamsen and I sparred. He thinks that the welfare of shrimp is so morally important that it may outweigh all human interests. He thinks that while it intuitively seems that the flourishing of every human being on Earth would be a good thing, we can only trust that intuition if we have good reason for believing the prior theoretical claim that “shrimp don’t matter.” But this gets it exactly backwards! Abrahamsen is placing the theory before the intuitive evidence. Instead of determining theoretically whether “shrimp matter” and then filtering our moral intuitions through that theoretical claim, we should consult our intuitions on clear cases and from there deduce plausible principles, but never hold a theoretical principle so strongly that it overrides a plainly clear case. I’m considering a world with flourishing for every person but 50% more shrimp pain and a world with misery for every person but 50% less shrimp pain. The former seems obviously better. People are capable of higher order goods so people are categorically more important than shrimp.

Key Takeaway #1: The right way to do moral reasoning is to start with a clear case and then figure out if a similar case should be judged the same way or if it is different in some morally relevant way. We rely on our intuitions in clear cases and also our intuitions about which factors are morally relevant.

Key Takeaway #2: Don’t become so wedded to your moral theory that you totally forget your moral intuition. If you find yourself saying that eating poop “certainly isn’t wrong” you might have missed something.

Some of the philosophers who think that moral philosophy should rest on moral intuitions (including Michael Huemer) call themselves “Intuitionists” but I’m not familiar with the details of their views, so I won’t use the term “Intuitionist” here. In this essay I am defending the form of moral reasoning described by Huemer in the quoted passage.

Singer, Peter. "Famine, Affluence, and Morality." Philosophy and Public Affairs, vol. 1, no. 3, 1972, pp. 229–243. https://rintintin.colorado.edu/~vancecd/phil308/Singer2.pdf

In my brilliant rebuttal to the Drowning Child argument, I argue (among other things) that some of those differences (which Singer says are morally irrelevant) actually are morally relevant. The distance between you and the child DOES matter morally because allowing people to die right in front of you would brutalize your heart. The reason why there’s a morally relevant difference between a distant death and an immediately present death is the same reason that there’s a morally relevant difference between a regular film and a snuff film.

I’m not claiming that the BLM riots and the Dublin riot are morally equivalent. Obviously, the Irish people’s self-defense against ethnic cleansing is not equivalent to the BLM rioter’s obsession over a fictitious epidemic of “racist cops.” But my point here is about the philosophical principle. If political rioting is justifiable, then it’s justified for the Irish and it would be justified for the BLM rioters if the BLM rioters were correct about the existence of an epidemic of racially unfair policing. But the commentary of White nationalists during the BLM riot wasn’t “these people’s actions would be justified if their beliefs about police corruption were true, but they happen not to be true” it was “law and order.” And the left-wing politician’s commentary in 2020 was not “yeah the police are evil so it’s morally acceptable to attack them” it was “people who would be driven to riot must be in a lot of pain, we should listen to them.”

Very interesting read! I broadly agree with Silas’ comment, and am collecting some of my own thoughts on the matter… Hopefully will be able to give a full write-up of where I am tonight, and/or maybe it will turn into its own post in a day or two.

I appreciate the response!

On the shit point, I honestly just don't find myself having an intuition that eating poop is inherently morally wrong. Maybe I'm just too lost in the sauce or something, but even when I try as best I can, I don't have any noticable intuition of wrongness about eating poop. I of course think its very imprudent, disgusting, and whatnot, but morally I don't see much of anything wrong with it.

Like, if I saw someone eating some shit, I would feel bad for them, and think that they were harming themselves, etc., but I certainly wouldn't feel the urge to punish them, or consider them morally blameworthy for what they did.

Of course they're doing the small harm of causing a disgust reaction in me, but that isn't something about the inherent wrongness of the action, so to that extent I'll agree that there's something *a little* wrong with it (as well as other side-effects like disease-spread and so on).

On the point about intuitions, I broadly agree with your approach, and I suspect we may have misunderstood each other a bit. I agree that we should start with clear cases, and work out a unified theory to accommodate these through reflective equilibrium, etc.

My point was simply this: Our moral intuitions are only about cases where the facts are held fixed, not about the actual world. Our intuitions about actual cases are contingent on what inferences we make about the descriptive state of the actual world, which are subject to revision--and descriptive evidence or moral theories cannot be overturned by our moral judgements in the actual world.

To illustrate: Suppose I see someone burning a child alive. I obviously infer that that is immoral. But that is only because I infer, based on my observations etc., that the child feels pain and whatnot. If I then find out that the child is a philosophical zombie, I revise my model of what the actual world is like, and the moral judgement I made prior to this new descriptive knowledge no longer has any weight for my actual valuation of the case.

It sounds to me like your disagreement more comes down to the fact that you think the shrimp-pain world isn't bad, regardless of whether it's the actual world or a hypothetical one. I of course disagree with this (I think other clearer intuitions, combined with things like scope insensitivity may undercut how much you should trust your shrimp-intuition), but that's more of a first-order moral disagreement than a methodological one, and I actually think we may agree more or less on the general methodology.